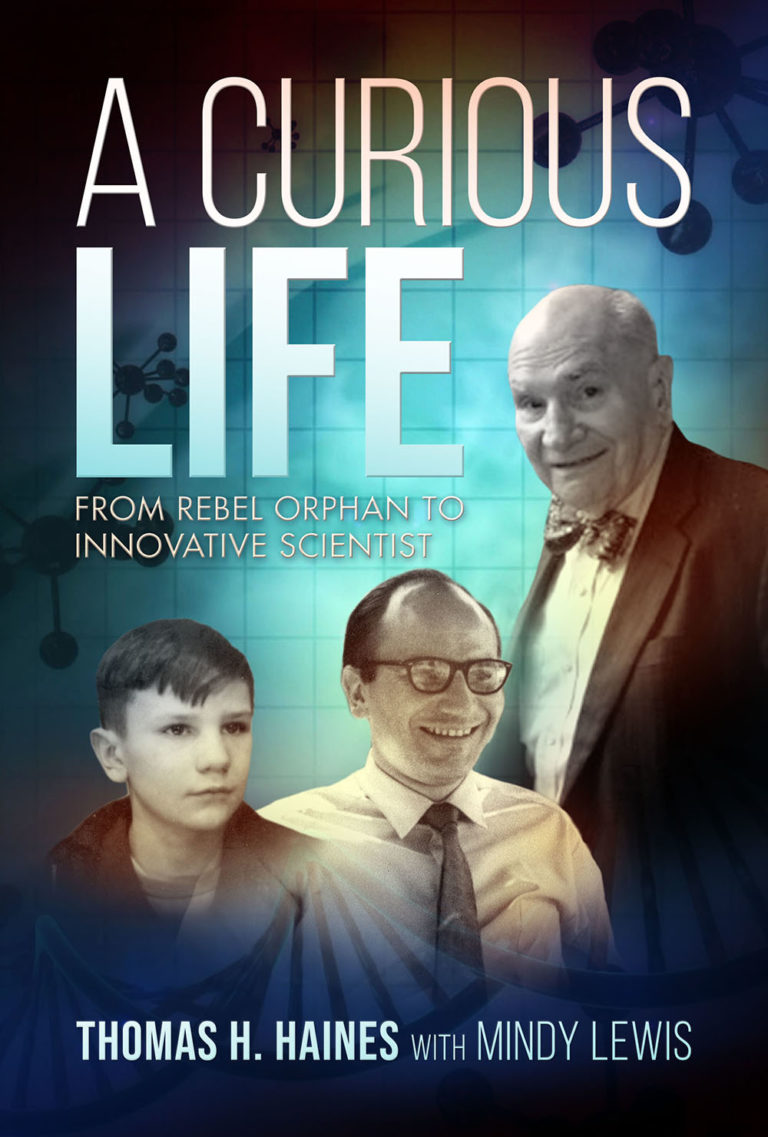

Bio

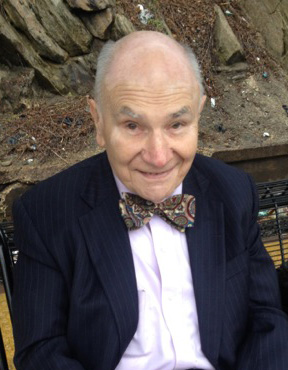

Thomas Henry Haines, a noted specialist in the study of lipids and biological membranes, is a Visiting Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Rockefeller University and Professor Emeritus of Chemistry and Biochemistry of City College of the City University of New York. In the early 1970s, he was instrumental in establishing The Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education at City College, where he taught biochemistry for 35 years. He received his B.S. in Chemistry from City College in 1957, his M.S. in Education from City College in 1959, and his Ph.D. from Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, in 1964. Dr. Haines and his wife Polly Cleveland live on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, close to Central Park, where he enjoys running each morning. He and his wife created the Danica Foundation, devoted to funding research in science and economics; he also serves on the board of Graham Windham Services to Families.

Thomas Henry Haines, a noted specialist in the study of lipids and biological membranes, is a Visiting Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Rockefeller University and Professor Emeritus of Chemistry and Biochemistry of City College of the City University of New York. In the early 1970s, he was instrumental in establishing The Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education at City College, where he taught biochemistry for 35 years. He received his B.S. in Chemistry from City College in 1957, his M.S. in Education from City College in 1959, and his Ph.D. from Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, in 1964. Dr. Haines and his wife Polly Cleveland live on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, close to Central Park, where he enjoys running each morning. He and his wife created the Danica Foundation, devoted to funding research in science and economics; he also serves on the board of Graham Windham Services to Families.